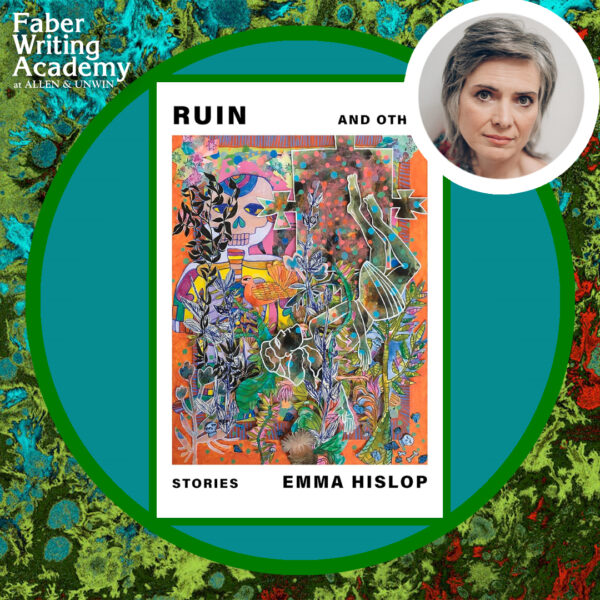

Emma will be teaching Short Stories: Disrupting the Process starting on 24 October, 2024.

The Game, Emma Hislop

Trigger warning: Sexual violence

‘He came into my room this morning in just a towel.’ Remi empties the food scraps into the compost bin, then puts the lid back on it. Her feet are bare and filthy. She and Jade have been building the chicken hut all day.

Jade bends down to pick a stone out of the freshly turned soil which is dusty and browny grey. She stares at the stone, then closes her hand over it.

‘I thought you said he was hot.’ Her voice is meaner than she intended. When he’d opened the front door of the flat just moments ago, she felt a pull in her body. Lewis. A mouth she’d like to kiss. Short dark hair and dark eyes.

‘He works at a school for emotionally disturbed kids. He sometimes has to restrain them.’ Remi looks at her muddy hands. ‘And he’s a Sagittarius. We’re going to the Tate next week.’ Remi is a Gemini and Jade is a Virgo.

The last boyfriend Jade had was an Aquarius. ‘Two overthinkers. You won’t have an easy sexual relationship.’ They’d lasted a month. That was a year ago and Jade’s only been on two Tinder dates since, both awful.

Jade pulls her ponytail higher onto her head then smooths out her fringe. She only helped Remi move in here two weeks ago. This is Jahna and Tom’s place. They’re Jade’s friends from work at the art studio. They had two rooms up for rent. Remi moved into one. Lewis answered the ad in the wholefood store window and moved into the other.

But Jade already knows how it ends. She’s known Remi longer than she hasn’t known her. Every time Remi breaks up with someone, she moves in with Jade, sometimes for days, sometimes for weeks. Jade’s flat is on the other side of the park and is tiny.

Lewis comes around the corner of the house pushing a wheelbarrow full of rubble. He’s tall, and a bit of a tattoo is poking out of his shirt sleeve. The courtyard is filled with yucca plants, and ceramic pots in varying sizes line the wall, some with plants, some waiting to be filled. Remi makes a show of pointing out the new flower beds to Jade, while fiddling with the strap on her vest top, letting it fall off her shoulder. The mounds of dirt side by side remind Jade of freshly dug graves. Lewis parks the wheelbarrow so it’s parallel with the fence and turns to face them.

‘Tom said this was a bomb site back in the day. Explains all the rubble,’ he says. There’s a spot above the corner of his lips, like a beauty spot that people sometimes draw on with eyeliner. It could be dirt.

Remi laughs like he’s said something hilarious. She walks over to the tomato plants held up with stakes in a neat row.

‘We should jump the fence at the Lido when it gets dark,’ she says. The Lido is the local outdoor pool, across the road from the flat. ‘Except Jade won’t come. She hates the Lido.’

Jade feels her cheeks go hot. She says, ‘I should just get over it.’ They’re both looking at her and waiting so she tells the story as fast as she can. She’s no good at this, despite having told it a few times over the years. It’s like Remi’s decided Jade’s the entertainment.

‘South London breaststroke final and I’m up against this girl from Dulwich, Ines Khan. It was a false start, but I got to the halfway rope and threw it off.’ She laughs, surprising herself. ‘I thought they were trying to stop me winning.’

He laughs and she laughs again, with him.

‘How old were you?’ Lewis says.

‘Fifteen.’

‘The stadium totally loved it, they cheered and cheered,’ Remi says, and twists off a ripe tomato. ‘She had to swim again. She loved it too.’

Jade can only remember the laughter while she walked back the length of the pool in her clingy, wet swimsuit. Remi is looking at Lewis staring at Jade and the energy is weird and the sun burns overhead. He bends down and turns on the tap by the compost bin. He splashes his face with water, then uses his arm to dry his face. The beauty mark is still there.

‘Please tell me this ends well,’ he says.

Remi picks up a bamboo stake leaning against the fence and jams it into the ground.

‘She won,’ Remi says.

Later, Jade and Lewis sit at a table in the courtyard drinking with Jahna and Tom. Remi’s not drinking – ‘just to try it out, for a bit,’ she told Jade. She’s grilling vegetables on the barbecue at the end of the table and has changed into a top that she’s wearing like a minidress. Jahna’s telling Lewis about the veggie co-op they belong to. The smoke rises up and drifts over the trees as though the city has taken a breath. The sky has dimmed to a deep blue and a few stars are appearing. People start arriving, with plates and pots full of food, which they put on the table. There aren’t enough seats, so some people sit on the lawn. At the table, plates are passed around and people fill them with food.

‘Wow, that okra.’ Remi is on Jade’s left, at the head of the table. The vodka’s gone to Jade’s head. She takes a bite of okra, then another. Lately she’s been too tired to cook for herself, picking up ready meals from the station on the way home.

‘I hope you’ve all got your tickets for the festival,’ Remi says.

Jade says, ‘I’m on the morning shift Saturday.’

She helps at the co-op on the weekends. During the week she works at the art studio. It covers her rent, but she needs to figure something else out soon.

‘Can’t you swap with someone?’

Remi gets an allowance from her parents. She works, but part-time, at a boutique store. Something touches Jade’s leg under the table, and she shifts slightly. There’s a hand on her knee now, not moving. Remi wouldn’t, would she?

The game started when they were ten or eleven. They called it Nuts and Bolts and they played it in the basement while Remi’s parents were upstairs. Remi would always decide the order of things when they played the game. Remi usually chose Jade to be the victim. The rules were no talking or eye contact. The rapist had to break through the door and pin the victim on the bed by the wrists and pull up their shirt and push down hard on their body. And say mean things. Jade always worried about being found out, but they never were. Recently, Jade found out that Remi’s mum Anita had been raped around that time. She’d been shocked about the rape, but also about the fact that Remi didn’t tell her at the time they played the game. It was, in fact, the whole reason they played the game. Remi was in therapy now and was working a lot of stuff out. By sharing her pain, she felt less pain.

‘No partying for me either, school reports to write,’ Lewis says. Both Remi’s hands are visible. A finger strokes Jade’s knee. Jade looks across at Lewis like she’s noticing him for the first time again. She smiles at him, and he smiles back. Around them, the others are laughing and talking. She looks down at the rapidly cooling okra on her plate and stuffs two pieces into her mouth at once. Tom reaches past her for a basket of bread.

‘Jahna and I are coming,’ he says. ‘There are some permaculture workshops this year.’ Her skirt is slowly being pushed up her leg from the hem. Something strokes the inside of her thigh. She moves her foot, not a kick exactly, more of a nudge and the stroking stops. She kicks harder and this time he starts kicking her back. Someone knocks over a glass of wine and she hears him say, ‘I’ll go. I’ve got it,’ and he stands up and leaves the table. A moment later she gets up and goes inside too. It’s dark in the hall and he’s standing on the stairs. She moves past him and their hips touch. He grabs her hand and laces his fingers into hers until they’re tight. Then there’s Remi’s voice from downstairs asking if they want dessert.

The café is cool and dark, relief from the heat that feels like it’s trying to submerge the city. Remi orders bubble tea. When the waiter brings them, Jade and Remi try them both and decide the white peach is the best. Remi slips out of her sandals and places her bare feet on the bench opposite.

‘We played that crazy game where you sit on someone’s shoulders and try to get the other person into the water. Oh.’ She stands up and pulls a small envelope out of her skirt pocket, then pushes it across the table. ‘He said to give you this.’ Then she sits back down.

‘He likes you. I can tell,’ Jade says. She fingers the envelope. She has this feeling she sometimes gets, like she’s a minor character in this play and Remi is the lead.

‘Aren’t you going to open it?’

Jade looks at Remi. She keeps looking at her.

‘The seeds will go everywhere.’

Remi sucks the last of her bubble tea noisily through the straw.

‘I better go pick up the car. I’m meeting the others in Croydon.’

‘Got your licence?’ Last year they caught the train out to the hire car place and Remi had left her driver’s licence at home and had to go all the way back to get it. Jade doesn’t drive. They’d got to the festival at midnight and the gates were closed and they slept in the car on the side of the road.

‘Ha-ha very funny. Wish you were coming, Jadey.’

They say goodbye at the corner by the wholefood shop. Jade walks home slowly. The air is thick and close, and loud ska music is coming from a little stretch of park where the roads converge. She pulls the envelope out of her bag and opens it. Inside is a packet of seeds with a picture of a velvety crimson flower on the front. Nasturtium, Empress of India. A tiny folded-up bit of paper falls to the ground. She picks it up and unfolds it. Call me. And then his number.

She tries to wait, to run into him at the pub, but hasn’t the patience. When she texts him, he replies straight away. It’s his idea to meet at the Lido. Cheeky fucker, she texts back: although she can’t be bothered thinking of anywhere else, she’s just excited to hear from him. Okay then. She puts on a cotton sundress over last summer’s red bikini.

He fingers her at the deep end of the pool, in the corner, against the ladder. He wants to fuck there, but there are swimmers in the next lane and there’s the issue of the condom. Thankfully, the men’s changing rooms are empty and they go into a cubicle at the end of the row. He takes her chin and tilts it towards his. As for what happens next, it isn’t really a kiss. He is biting her lip and their teeth knock together and she is sure she tastes blood. For a moment she cannot breathe, but then their tongues establish contact. He pulls down his shorts and she starts to take off her bikini pants, but he turns her around so she’s facing the wall and tells her to keep still. Her phone rings. She thinks about Remi while he rolls the condom on, then she thinks about nothing. Remi is at the festival. He pulls her pants to the side and gets deep inside her.

Afterwards, they walk to his and Remi’s flat. The afternoon sun is baking. His bed is a futon on the floor, with fresh-looking white sheets and there is a big floor-to-ceiling window overlooking the park. There’s nothing else in the room except for a stereo and a wooden clothes rail hung with clothes. They get into bed. He brings his face close to hers, then waits for her to kiss him. He doesn’t initiate anything else, and she’s partly hurt, and partly relieved. It felt familiar. It was like being with Remi. The feeling of someone having power over her, in a way that seems playful at first, but isn’t, not really. She lies with her face in the pillow, and they fall asleep and when she wakes up the light has changed, but it is still light. She wants to have sex again, but Lewis is still asleep. She wraps a sheet around her body and goes into Remi’s room and looks in the wardrobe. She chooses a gold silk top with long floaty sleeves she hasn’t seen Remi wear before. She puts it on and looks at herself in the mirror. Her mouth looks swollen and sore. Out the window she can see the new flower beds, bordering the square patch of grass.

‘The traffic on the M1 was backed up forever. We only just got the car back in time,’ Remi says.

The longer Jade doesn’t say anything about Lewis, the worse it’s going to be when Remi finds out. But she wants to keep it to herself for a bit. She still smells of him. She and Remi are sitting at the kitchen table, drinking coffee, and flicking through their phones. The doors are open to the courtyard and sunlight is pouring into the kitchen.

‘I texted him from the festival and told him to water the tomatoes and he sent a kiss back,’ Remi says, and pours more coffee into her cup. ‘The photos of the main stage are way better on my laptop.’ They hear the front gate open, then someone coming up the side of the house. He’s carrying a big cardboard box, so big only his lower body is visible. There are ventilation slits in the sides of the box.

‘Chickens!’ Remi says. ‘Hello!’ She gets up and goes outside. Jade stays where she is, on the chair, in the patch of sunlight, and pretends to look at her phone. She hears him say something, but she cannot hear all of it and then she hears the sound of the box being opened, maybe with a pocketknife.

Remi says, ‘Jade, come and look.’

Jade goes outside and stands a little bit apart from them. Lewis takes the birds out of the box one at a time and puts them over the fence into the run. Two of the chickens have lost feathers and have bald patches on their heads and necks.

‘Poor little things,’ Jade says, staring at the birds.

He looks at her and nods. ‘We’ll sort them out, Jade. You planted those seeds yet?’ He knows she hasn’t.

‘How are those reports going?’ Jade says, but she’s not into the joke, she can’t keep this up much longer. She wants to have the conversation with Remi about the game.

Remi says, ‘Yeah, how are those reports going, Lewis?’ and goes inside to get her laptop.

He comes over to Jade and pins her there against the fence, his arms on either side of her. She can feel his hard stomach under his T-shirt. For the first time she doesn’t need permission. She grabs his T-shirt in her hand and pulls him towards her. When she looks up at Remi’s open bedroom window there is a movement, but she could be imagining it. She should move, but she doesn’t. She kisses him, hard. Then she wipes her mouth with the back of her hand.

‘What do you need to tell me?’ Remi says, scattering the pellets. The dust from the pellets makes a blanket over the bird’s feathers and then, when it shakes itself, forms tiny tracks in the dirt below.

They could talk about Lewis another time. Remi would cope. The sun is very hot.

Jade runs it through her head again. ‘I wanted to talk to you. About the game.’ Remi always initiated it.

‘What game? The other one must be somewhere. Can you have a look?’

Jade unlatches the door of the chicken hut and peers into the darkness. ‘It’s here.’ It doesn’t move. She keeps looking at the bird until her eyes adjust. If it wasn’t for its swollen claws and cloudy eyes, it could just as easily be sleeping.

‘You were always getting me to play that Nuts and Bolts game.’ She can’t see Remi’s face from here. It was the way they had always done it, that Jade was ready, whenever Remi initiated it.

Remi puts a container of water over the fence, knocking it sideways.

‘It was nothing, Jade. We were kids.’

‘I think it’s dead.’ Jade stands up and looks at Remi. ‘It wasn’t nothing though, was it?’ She remembers the feeling of Remi’s bed, the restraint of it.

‘Gross!’ Remi shakes her wrists up and down, splattering water on her shirt. She’s hard to read sometimes, even after all these years. ‘We didn’t do anything wrong, Jade. It didn’t mean anything.’ She laughs.

‘Why is everything a joke with you?’ Jade considers the possibility that it meant something different to Remi, and now, faced with it, she doesn’t know where to take it. ‘It wasn’t nothing.’

Remi shades her eyes with her hand. Her fingernails are painted a matte pink.

Jade says, ‘If I’d known then, what had happened to your mum . . .’

Remi flinches. ‘Don’t put that on me, Jade. You didn’t have to. You participated.’

‘Maybe I didn’t have it in me to say no. I was a kid.’

Remi wraps her arms tightly around her torso, like she’s trying to keep herself warm. ‘Why are you making me feel bad?’ She’s lost patience with whatever is going on here.

Jade picks up the bird and props it up on a shelf of branches, where, she hopes, the flies and ants will get to it first.

‘That’s stupid,’ Remi says. ‘Leave it. The other chickens will eat it. I saw it on a nature programme.’

When Jade turns around Remi is standing there. She seems to have made up her mind about something.

‘It was my idea. Lewis didn’t do anything to you that he doesn’t do to me.’ She grabs Jade’s hand. ‘Or did he restrain you?’

Jade stares at Remi, trying to figure out what she means. Neither of them says anything for a moment. What does she know? She knows.

Remi says, ‘It was obvious you couldn’t give him what he wanted.’ She laughs. ‘Poor Jadey.’

An ornate merry-go-round has been set up near the Herne Hill entrance to the park. A group of face-painted kids are waiting for it to open. Tents and stalls and parked vehicles line the main path up the hill. To the right is the main stage, covered in brightly coloured bunting and flags. A samba troupe in matching brown-and-gold T-shirts are keeping rhythm on the stage, their huge drums held against their bodies with wide red straps. The smell of jerk chicken is in the air. The crowd is already big, and it isn’t even midday.

Further up the hill, past the Punch and Judy booth, are the fruit and vegetable sculptures. A scene from King Kong, made entirely from carrots, the cast from Sesame Street, a domestic violence scene entitled ‘Arty Choke – it is never okay’. Boris Johnson, his deep purple tuxedo carved from an eggplant, with a pineapple collar and red capsicum skinny tie. Next is the main arena, where the sheep shearing and the Best in Show will be held. At three o’clock, a crowd will gather for the popular Flight of the Falcons display.

The jerk chicken stall is set up behind two parked trucks. The oven is a rusty 44-gallon drum turned on its side. A man stands behind it. He is wearing a green T-shirt with Jamaica on the front in yellow letters and a heavy-looking gold chain around his neck. He is turning the charred chicken with a pair of tongs and holding a water bottle in the other.

A bird man on stilts teeters past in a multi-coloured cloak of painted feathers and an elaborate headdress. He has enormous blue rubber hands, and he is waving them from side to side. A girl wearing a T-shirt that says Bubble Inc. on it is next, trailing a gigantic bubble behind her stretched out on a stick frame. A crowd of kids dance around her, mesmerised by the scale of it and the oily pinks and blues on its surface.

Remi and Lewis are standing in the Organic Produce arena, behind a wooden table covered in vegetables. There are people everywhere. Remi’s wearing the gold silk top and looks very young, somehow. Lewis is talking and Remi looks like she is listening but she’s not saying anything. He bends down and kisses her on the mouth. Jade slowly makes her way over between the tables and stops at the one next to them. She leans over, pretending to look at an eggplant. Remi comes over and stands in front of her and it’s as though they’re both holding their breath. Remi lifts her arms out, as though she’s going to touch Jade and the sleeves on her top slide up her arms and there are marks on her wrists. She laughs. Then Lewis’s arm is at Remi’s waist, propelling her away, but she breaks free and merges with the crowd. A kid in a skeleton costume runs past, chasing a red balloon, but it must be helium because it goes up into the sky.

This course has one scholarship place available for a writer who would otherwise not be able to afford to attend. Applications from people who identify as diverse (eg. Indigenous, minority ethnic background, LGBTIQA, living with disability) are especially welcome.

To apply, please submit a link to a published story, along with a cover letter outlining why you are interested in the course, and how you would benefit from the scholarship. Please address applications to Pip Smith at faberwritingacademy@allenandunwin.com, with the subject line ‘Scholarship Application: Short Stories, Disrupting the Process’.

Applications for this scholarship will close on Tuesday 1 October 2024.

Bookings are currently open for our Short Stories: Disrupting the Process course Emma Hislop.

Short Stories: Disrupting the Process

with Emma Hislop

ONLINE

Thursdays, 7.30pm – 9.30 pm NZST

24 October – 5 December 2024